I'm working on solving the mystery of why money supply stopped plummeting, starting in May 2023. I suspect this event had something to do with the shift from rapid disinflation to very slow disinflation a few months later.

So how is money supply no longer going down as rapidly as before, despite an unchanged $95B/month rate of QT?

Many of us exposed to political talk would cite the federal budget deficit and say that in 2023 it represented $+1.69T in money printing, offsetting the 95B*12= $-1.14T per year in QT for an expected net gain of $+550B to the money supply in 2023. However,

M2 actually declined by $470B from January 2023 to January 2024.

M1 declined by $1.58T in the same timeframe. There seems to be at least a trillion-dollar leak in this simplistic theory.

Wolf Ritcher of the Wolf Street blog reports some points I might use to at least partially plug this hole and explain more parts of the bigger picture of money supply and inflation.

As we know, the Federal Reserve sits on a massive pile of treasuries, many of which were purchased when interest rates were very low - the years after the GFC and during COVID. The Fed receives interest from the Treasury on their bonds, which includes lots of low-yielding long-duration bonds. These interest payments, on net, show up as part of the national deficit, even as the government is paying them to itself.

On the other hand, the Fed pays interest on reserve balances that banks must keep at the Fed, and the Fed also pays interest in overnight repo markets. The Fed's own interest rates have bumped this interest rate to 5.4% and 5.3%, respectively. So when the Fed is earning maybe 2% on a treasury bond bought long ago, and paying 5.4% on reserve balances, the Fed reports a "loss". Yes, this is the government printing money on the one hand and saying they lost it on the other hand, but let's go ahead and pretend because this activity is consequential to the amount of cash in the economy. Fed "losses" represent net interest received by somebody in the market - probably a bank which uses it to create even more money supply through loans.

Thus, when the Fed is holding long-duration and lending short-duration, an inverted yield curve leads to the Fed injecting money into the markets via its deficit in net interest.

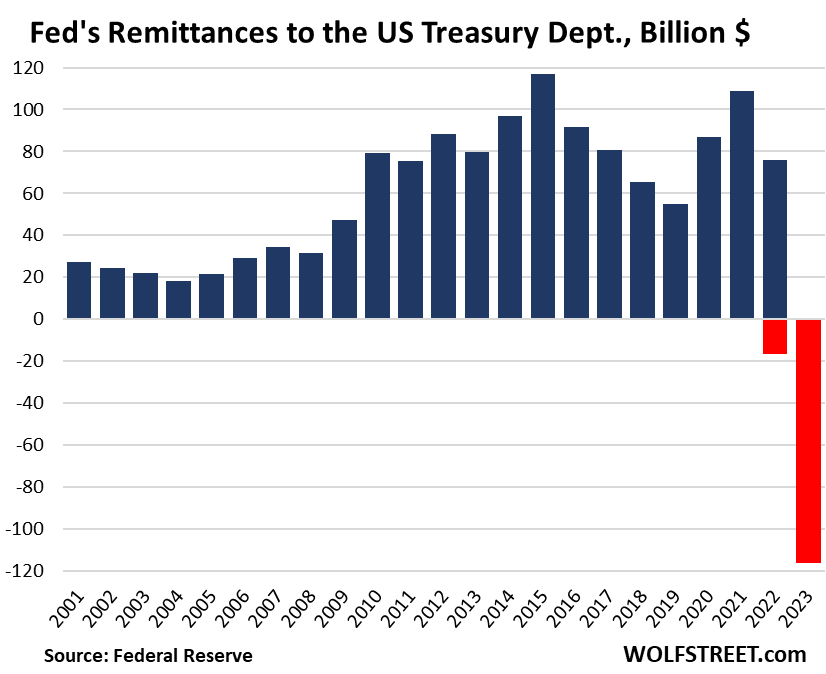

Wolf Street reports the Fed's interest expenses increased 175% in 2023, and that the Fed "lost" $114.3 billion on net by paying that much more in interest than they received. The Fed usually remits "profits" to the Fed, but due to the inverted yield curve they are instead making big losses:

These "losses", $130B across 2022 plus 2023, represent a form of stimulus or QE, and should be expected to contribute positively to money supply to the extent they are paid to banks, governments, or private parties. Thus as the Fed's interest expenses and "losses" grew, this was essentially the injection of billions of dollars into the economy, just like QE. Also note that when the Treasury stopped receiving remittances from the Fed, they had to plug that hole in their budget by borrowing / printing more money, which resulted in them paying even more interest cash to the often-private holders of those treasuries.

So to some extent, the government's $947.6 billion dollars in 2023

interest expenditures represent expansion of the monetary base.

Now we're very close to explaining the gap between QT, deficits, and money supply shrinkage! It's government interest payments!So even though the Fed's losses only explain a small percentage of the change in money supply, they lead us on a trail that suggests the massive amount of spending on interest is a form of QE rivaling and offsetting QT. Inflation may be flatlining or rising again because these factors are keeping money supply high.

This represents a change to our whole model of inflation and intervention.

In a world where the Fed is engaging in massive overnight lending to control interest rates, and where the treasury owes nearly $35T in debt, the government's efforts to raise interest rates will result in hundreds of billions of dollars in money supply injected into the system. I.e. the government has to pay that interest into people's pockets. Thus rate hikes now have both a restrictive and stimulative effect, whereas in the past they were much more restrictive. They're constraining consumption and business investment with rate hikes while at the same time pouring money into the market with higher interest payments.

So are there any plans for the government to pay less in interest anytime soon? If so, that would contribute downward pressure on money supply, and the monetarists among us might expect inflation to resume falling.

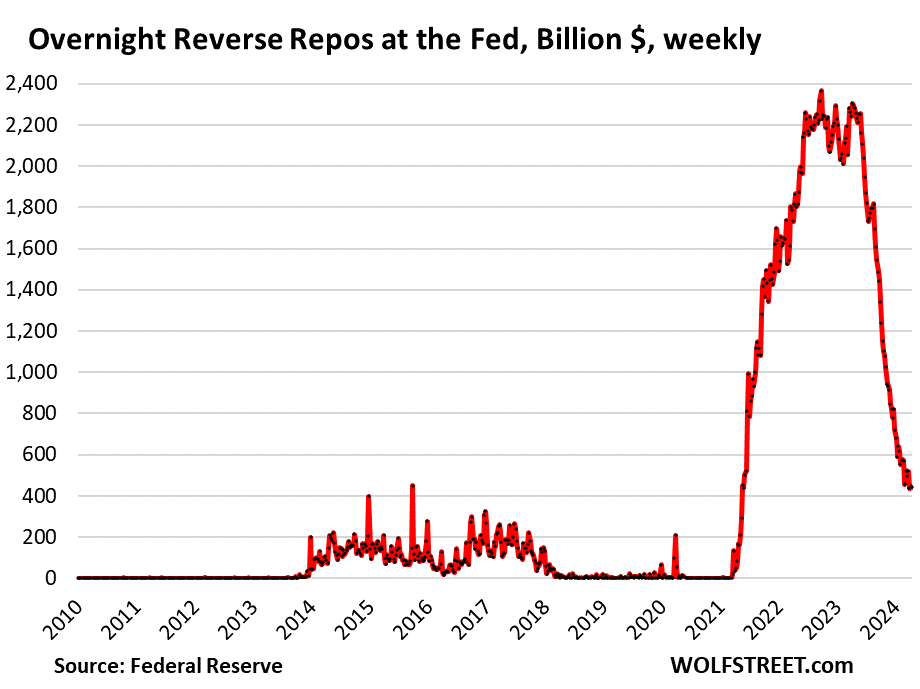

According to Wolf Street, the Fed is expected to wind down their overnight reverse repo market. This market is already $1.9T smaller than it was, and is down to $441B. That's a lot of 5.4% interest the Fed won't have to pay!

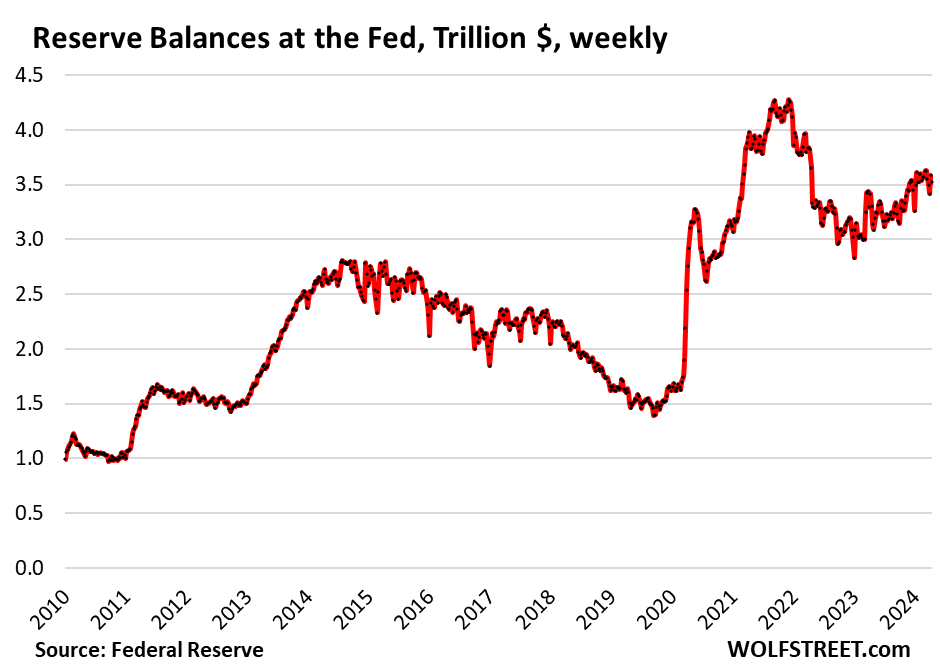

Wolf Street expects Reserve Balances to fall after the overnight program goes to zero, as QT removes excess cash from that market. Some money leaving the overnight repo market ends up here, but not enough to offset QT.

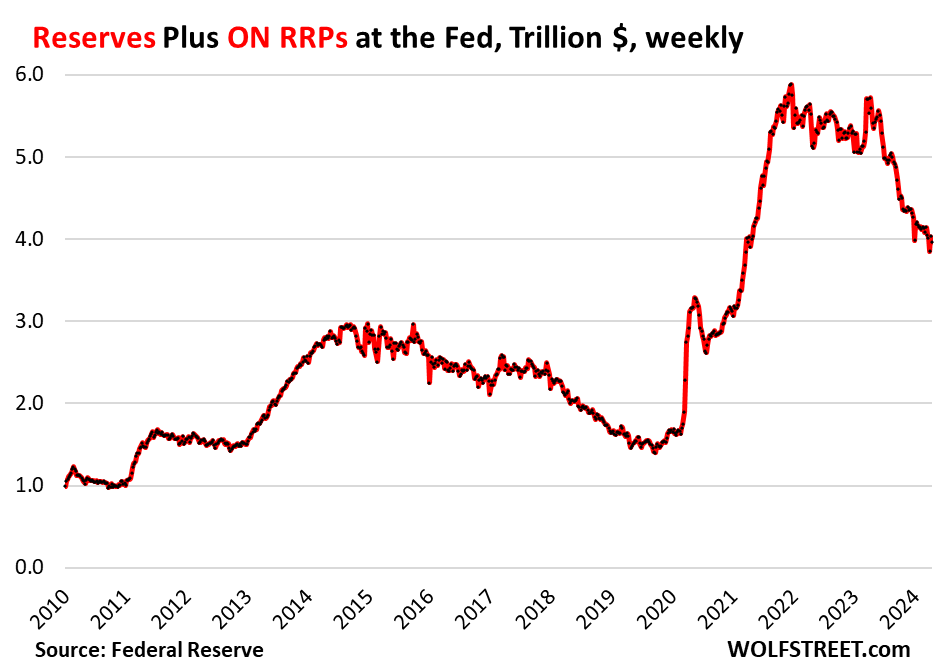

The overall amount the Fed pays interest on - overnight repos plus reserves - is falling rapidly. This number is down almost $2T since the peak in December 2021.

On the flipside, the Fed will be earning a bit less interest as QT winds down its balance sheet. But the net flow of interest cash to the market will be reduced.

HOWEVER, this is just the tip of the iceberg we're talking about. The Treasury will keep paying high interest rates, even after rate cuts begin. We could be in a situation where the deficit is so large, and high rates contribute so much to money supply, that raising rates to the mid-single-digits no longer works for inflation control or GDP reduction.

The FOMC might be operating on a playbook that was relevant for earlier times or lower-deficit times. So their response might be to hike rates even further, in reaction to the money supply growth caused by their own rate hikes. Perhaps this is why GLD is up 17.3% over the past 6 months.